We’re launching Lunette: a platform that uses investigator agents to audit your AI agents and environments. Lunette answers questions like: why does my agent fail? Are there bugs in my eval? What behavioral patterns emerge across tasks?

Issues in agent evals are wide-spread. Even SWE-bench Verified, the most popular software engineering benchmark, human validated by OpenAI, has unsolvable tasks that are therefore useless for understanding an agent’s abilities. We used Lunette to find issues in SWE-bench – see a live demo here.

It’s hard to understand and debug AI systems. Agent generalization is spiky: they fail in ways that are hard to anticipate. The transcripts you have to read are long but low-signal. Production data is very different from eval data, and changes often. AI systems need a new kind of debugger.

Lunette uses investigator agents that re-enter the same environment that your agents ran in. That allows them to run experiments that tell you why your agent fails or whether your environment has any bugs. These investigator agents can also double as powerful graders, equipped with the context to accurately judge agent traces.

Try Lunette now — your first 40 investigations are free. Book a time here if you want to scale your usage.

How Lunette works

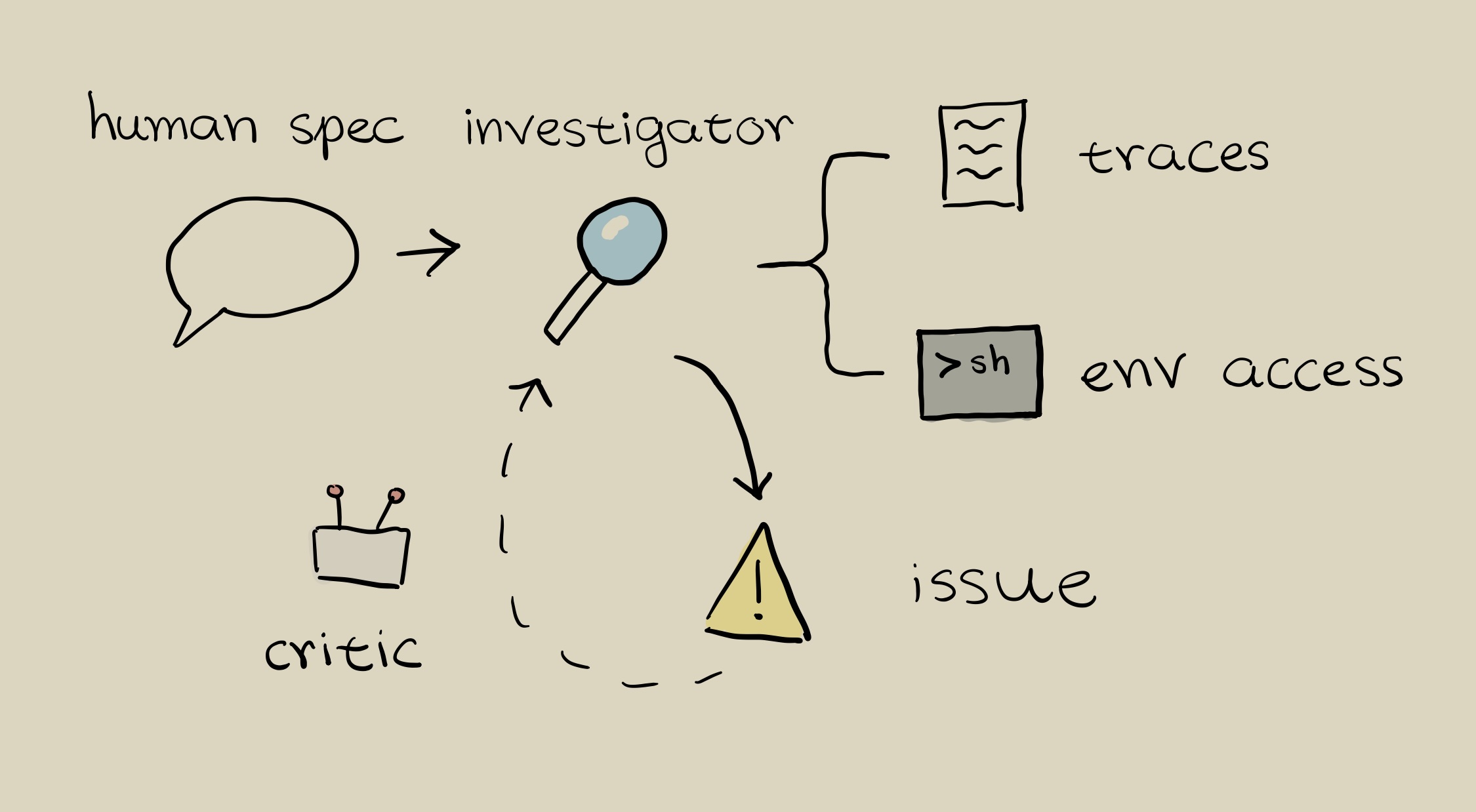

Users start out by providing Lunette with investigation specs for agents or evals they want to understand.

Lunette then launches investigator agents that operate in parallel. For each trajectory, an investigator agent

- reads the agent trace

- modifies and runs commands in the eval environment to test hypotheses

- writes its findings

Every finding is then critiqued and filtered for quality. At the end, users can explore investigation results in Lunette, or use a chat interface to better understand their results.

Why Lunette works

LLMs analyzing or judging agent traces tend to confabulate: they’ll confidently explain why an agent failed based on plausible-sounding but wrong reasoning.

Lunette’s investigators are harder to fool for two reasons.

- Environment access: instead of reading a trace and guessing, investigator agents can run experiments to test hypotheses

- Validation: investigators produce evidence (command outputs, file contents, test results) that validator agents independently check. Validators verify whether evidence actually supports a conclusion, rather than just evaluating whether an explanation sounds reasonable.

Validating Lunette by finding broken tasks in SWE-bench verified

To validate and improve Lunette’s investigators, we manually found issues in SWE-bench tasks.

Some SWE-bench background: each SWE-bench task is a resolved GitHub issue from one of 12 open-source Python repositories. Each task has associated FAIL_TO_PASS tests (which the solution must fix) and PASS_TO_PASS tests (which verify nothing else broke). Agents are given the issue text and codebase, but not the tests. Both test sets must pass for a task to be marked resolved.

The core, repeated problem is that the FAIL_TO_PASS tests aren’t necessarily specified by the issues, since they are often provided by the implementer of the PR alongside the updated implementation.

This was, of course, the motivation for developing SWE-bench Verified in the first place, which used human validators to filter out problems with:

- Overly specific unit tests

- Underspecified issue descriptions

- Difficulty with environmental setup

In our investigation, we found that many of these issues persisted even after filtering from human validators. To generate an eval set, we manually looked at and understood various Django tasks, and labeled them with issues and whether they were impossible.

We then ran Lunette on this eval and compared it to two baselines: Lunette without environment access, and a transcript-only reasoning model with the same base model and prompt. Environment access provides a significant boost—Lunette’s accuracy drops from 82% to 63% without it (see fig. 1).

See below for more examples along with Lunette’s outputs, and try it out now on your own data.

Examples of SWE-bench issues

Most problematic tasks are ill-posed, in the sense that there simply isn’t enough information in the task description for the agent to solve the task in the intended way. (We only found one example of a well-posed yet problematic task; its tests were too lenient.)

The ill-posed tasks we reviewed can be classified into two groups.

-

Problem descriptions that are too vague to clearly identify the intended solution. In these cases, the desired behavior of the code wasn’t specified in the issue report, but instead it was only decided upon in the subsequent discussion.

Example: django__django-11964. Lunette output. The bug is that TextChoices and IntegerChoices enum fields return different types for created versus retrieved model instances. When a model instance is created with a TextChoices or IntegerChoices field, the field value is an enum instance (e.g., MyChoice.FIRST_CHOICE), but when the same instance is retrieved from the database, the field value becomes a plain string or integer. This inconsistency particularly causes issues when using str() on the field value or rendering it in templates, where created instances show “MyChoice.FIRST_CHOICE” while retrieved instances show “first”. The fix adds a custom str() method to the choice enums to ensure consistent string representation.

The PR discussion reveals this task is problematic because there are seven different proposed solutions with fundamentally different intended behaviors. The developers debated whether to: (1) keep enum types everywhere, (2) convert to primitives on save, (3) convert in field descriptors, (4) override str() on enums, (5) convert in to_python(), (6) use a proxy object, or (7) document the current behavior as intended. The agents have no way of knowing which of these solutions is expected of them.

-

Tasks that have tests that are so strict they rule out valid solutions.

Example: django__django-11790. Lunette output. The bug is that the client-side username validation in AuthenticationForm.UsernameField is broken, always using a maximum length of 150. This is because the maxlength attribute in the corresponding HTML widget is not set at initialization. The solution is a one-liner setting that attribute.

In our experiments, all agents successfully diagnose the bug. However, they all fail to complete the task, because they set the maxlength attribute to a

strinstead of anint, as the tests expect. Since previous versions of Django had set that same HTML attribute to astrand the rendered HTML is the same either way, we think this task is problematic and all agents should have passed this task.